When I’m not working, playing squash, or spending time with my family, I’m a spy. At least, that’s my fantasy. Except I left my native England and took American citizenship. They don’t tend to recruit many deserters to MI6 and I’m yet to get a call from Langley to join the CIA.

Their reticence is also understandable given my big mouth. But that doesn’t prevent me from living a fantasy life. I spent the holidays re-reading Ian Fleming’s James Bond novels in order. I interspersed them with John Le Carre’s books, which are a lot tenser and have fewer gadgets in them. We watched a two-season-long Finnish drama about a secret spy organization. It’s called Shadow Lines and available on Sundance in case you’re in the market.

I love spies!

Not only that, but since COVID, I’m always looking for more spies. It saddens me that there is only so much spy content out there. I’ve watched Homeland four times from start to finish. I’ll often spend two and a half hours working with Timothy Dalton in The Living Daylights on. He can work in the background. It doesn’t matter if I tune in or tune out because I’ve seen it so many times, I can always pick up the plot anywhere. I know that if I watch the whole thing, I’ve concentrated for almost three hours. I can recite the whole film, almost, without it even being on. It was the first Bond film I saw in a cinema in 1987 before the Berlin Wall came down. There was something about its optimism mixed with the A-ha theme tune that snagged me.

Alright, I hear you asking. But: What’s any of this got to do with strategic communications? Well, first, if you’ve been subscribing to this thing for any period, you’ll know I’m a dab hand at shoehorning. What does anything have to do with strategic communications? Ha! Apart from the fact that I do it for a living and I guess anything I happen to take an interest in must inform my approach. So. There’s that. But. There is something useful in writing like a spy. Spies need cover. They must have a “legend.” A story that they can present to the world which explains what they are doing, and why. It’s particularly true if what they’re doing might alienate certain people.

The more time I spend helping people craft their own narratives the more I find myself thinking like a spy. I ask myself “who’s the enemy?” And “what would it take to persuade them to go along with what we’re doing?”

Can you get there, now? Do you catch on to what I’m suggesting? Are you the best person to approach a journalist with your message or might it be better for us to send a “cut-out” on your behalf?

This isn’t nefarious. Perish the thought. But it is exciting. It’s like throwing your hat onto the hat stand as you walk into the boss’s anteroom. It’s not that good communication is about lying. It isn’t. But there’s always the best way to portray your efforts in a way that most advances your cause. It’s the extreme effort that goes into doing that, while making it look effortless, that I love about spies.

They take their legends with the seriousness they deserve. If only we could all take our key messaging frameworks to heart at such a level. You might think Mr. X is going for a walk and happens to bump into somebody. It turns out he was doing a “treff” with some microfiche containing life and death secrets. Likewise, it might seem like your effortless press conference just came together. But somebody needed to decide between dozens of competing priorities. The journalists don’t see any of that.

Right. That’s quite enough from Double-Oh-Davis, for the time being. License to kill…your strategic communications. If by “kill” you mean “reinvigorate” and “make far more engaging.”

If you want to make my year, send me a red-bound book with various letters ringed to spell a sentence. Something like “Matt you’re a genius” or better yet, the location of the keys to a safety deposit box. Meanwhile, I’ll be here. You know. Pretending to be a civilian. Wink wink.

M

P.S. Here are five obscure spy books I’d like to recommend. They’re off the beaten track, so I hope finding them will feel like stumbling across a dead-drop in East Berlin. Leave a chalk mark on a lamppost when you’re done.

Berta Isla by Javier Marias—about a Spanish spy who goes undercover so long he’s presumed dead. It’s told from his wife’s perspective.

Sweet Tooth by Ian McKewan—about a writer recruited to spy from the University of Sussex, where I went.

The Man Who Loved Dogs by Leonardo Padura—about the man who killed Trotsky. Afterwards.

Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper by Fuschia Dunlop—a culinary memoir by a Brit living in China. I love it because the author muses for one sentence about how people often wonder if she’s a spy. I have since constructed a whole second life for Fuschia Dunlop in my head. I think it would make a fantastic basis for some new spy content.

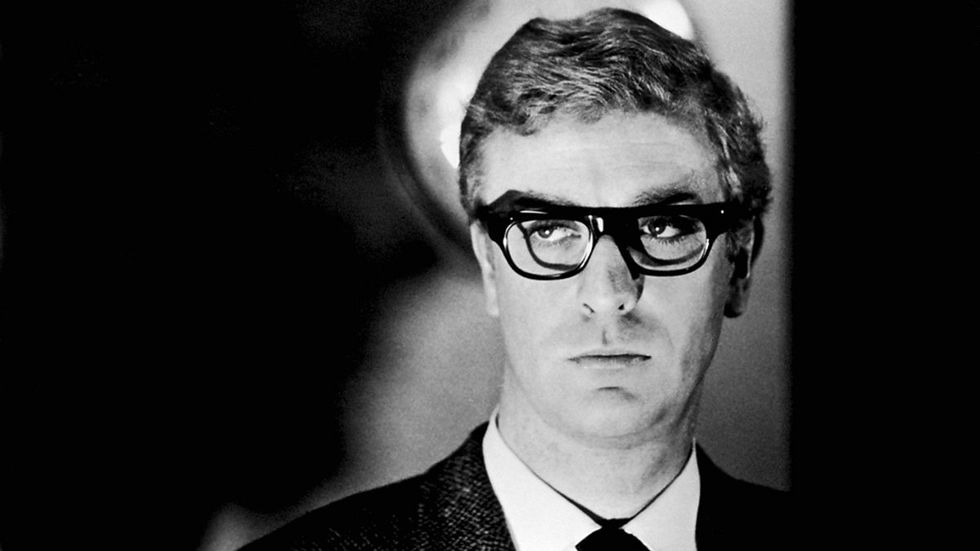

The Action Cookbook by Len Deighton—actually, not a spy book. But a series of graphic recipe strips by the later writer of The Ipcress File, (*source of the image above) which ran in London’s Observer newspaper. In postwar Britain one of the bravest things a man could do was…learn to cook. Deighton, one senses, was trying to figure out what he was doing, creatively, and with those impulses, with these strips. They’re experimental, graphically engaging and still quite good as recipes. The film version of The Ipcress File showcases an anti-James Bond in Michael Caine’s sensitive cook spy. The best part of getting a pay rise is he can buy a new “infra-red grill.” I absolutely love that scene. And this book weaves together a lot of disparate threads for me. The baked Alaska strip is amazing. It says to heat the oven up so much “it’s about to go into orbit.” It’s a marvelous piece of phrasing I often strive to re-use in other contexts.

Enjoy.