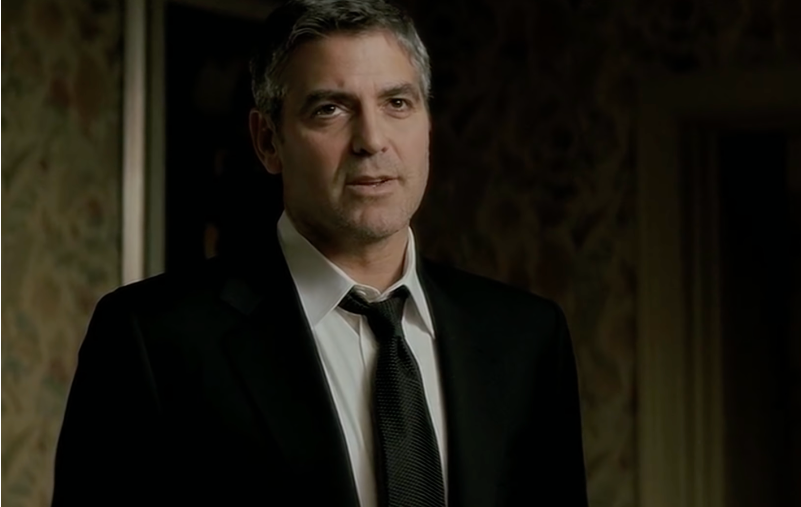

Image Caption: George Clooney as the “fixer” attorney in Michael Clayton

My wife and I have watched the movie Michael Clayton more than 50 times. Other people calm down by taking a soothing walk or watching the birds. We like to watch high stakes legal thrillers written by Tony Gilroy. Each to their own, I guess.

The acting by Tilda Swinton, George Clooney and Tom Wilkinson is all [*chef’s kiss] brilliant. My favorite scene is this one and it’s also a great crisis communications training!

Clayton, a fixer for a Manhattan law firm, gets a call from a colleague. The colleague works for a long-time client of the firm who’s hit somebody in his car in the street. The client is worth “half my book, this guy,” so Clayton drives up to the man’s house in Connecticut to try to sort things out. When he gets there, he walks into a mess. The client is erratic and dishonest. He’s a jerk. Clayton tells him, “Your options here are going to get smaller very quickly.” Then he tells him, “I’m not a miracle-worker. I’m a janitor. The math on this is simple. The smaller the mess, the easier it is for me to clean up.”

And that’s it. That’s crisis communications in a nutshell. By the time you’re in a crisis, the job of a crisis communications consultant is to clean it up. Another example is Harvey Keitel playing Winston Wolf in the movie, Pulp Fiction. “I’m Winston Wolf, I solve problems,” he says, as the front door opens on a graphic and remarkable crisis. It makes for gripping viewing.

My first rule in such a situation is to tell everybody to take a deep breath and stop. If it’s possible. Don’t make a crisis worse by trying to clean it up without thinking. Then, I walk them through the following questions to avoid pouring gas on any fires:

1. What immediate steps should you take? Should you be proactive? Should you be reactive? Hint: Doing nothing is often better than doing anything unwise. But don’t let paralysis prevent you from apologizing if it’s the right thing to do. Apologizing fast is often a key component in managing any crisis. And the slower one is to do it, the bigger the crisis becomes.

2. What do you know right now, and who else knows anything? What do they know?

3. How far is this going to go and what are the stakes? Who will it affect?

4. What do the lawyers say? What do they say you can and can’t say?

5. Who else needs to hear about this as soon as possible? Your board? Your staff? Your constituents?

6. What’s the best way to communicate with them?

7. What’s the most important thing to say right now? How will we say it?

Excellent. You should be able to get the quick version of those questions answered in fewer than 10 minutes. Then you can get an action plan in place to get to work. Crisis communications is a job I enjoy, and it flexes a skillset I’ve learned over 43 years. I wish I didn’t have it, sometimes. It can be exhausting to try to enjoy life when you’re always looking up to see where the exits are. Who’s covering the door? And so on. But I like the ability to use such skills to help people manage through difficult times.

It does help, too, to prepare for a crisis by thinking through the likely ones in advance. Call it scenario preparation. Think about where your risks are. Talk through each, conduct a mock assessment, and agree on a plan of action. I heard an illustrative story recently about a high-ranking government official. They have a filing cabinet with folders inside for each of about a dozen possible crises. If an earthquake hits, the first thing they do is open the filing cabinet and go to that folder. What was the first thing I thought when I heard the story? I thought: “An earthquake would break their filing cabinet.”

As I say, my brain works like a lizard’s. The best thing I can do (apart from plenty of yoga) is use it for a good cause!