In 2012, I went to Harry Connick’s house in New Orleans. I was there to ask the former District Attorney, and father of the jazz piano player, Harry Connick, Jr., about his office’s history of withholding crucial evidence from the defense, in the context of a story I was writing about a man subsequently freed, half a decade later, by the Innocence Project of New Orleans. Mr. Connick told me that the number of wrongful convictions under his office was “miniscule” compared to the total number of cases handled in his office, and that the number was “not remarkable.” The only pattern his office had was for “hard work, trying a lot of cases, getting a lot of convictions, answering the appeals, and losing very few of them,” he said. He was on the record. But the thing I remember most about our interaction, if I’m honest, are his scrupulously good manners. When it comes to influencing behavior change in Louisiana, I realized traumatic realities are challengingly interwoven with complex cultural norms.

Driving South through the United States this past weekend I noticed subtle differences in Coronavirus messaging on the highway signs. In New Jersey signs advised drivers to “CHECK QUARANTINE STATUS” and reminded them, “MASK REQUIRED.” In Delaware and Maryland the messaging shifted slightly, placing more power in the driver’s hands. The signs said: “PRACTICE CORONA COURTESIES: SOCIAL DISTANCE” and: “MIND YOUR CORONA MANNERS.” In Virginia one of the first signs I saw by the road after one welcoming us to the state was a painting of a Native American man, promoting cheap cigarettes.

My friend George Ames works for Forster Communications in London, and he wrote a blog on behavior change recently, although I would warn American readers that he’s talking only about giving up smoking when he refers to “ditching the fags.” For behavior change to happen, George tells us, “cultural norming” is required. If you’re aiming to give people an incentive to wear a mask in Delaware or Maryland, then it’s best to do so in the context of cultural norms like good manners. Whereas in New Jersey, people are more comfortable with blunt directness. For example, they recently trialed road signs there, telling people not to be “knuckleheads.” George says leadership and permission are two other crucial ingredients for change. That’s why it helps for the Texas Governor to say “leaving the house without a mask on is the equivalent of driving drunk.”

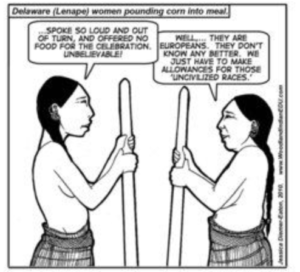

Manners are cultural and they can cover up deeper issues like racism. This cartoon* featuring two topless Delaware Native American women pounding meal into corn, and criticizing white Europeans for their lack of civilization at a celebration meal is a good reminder.

I’m also fascinated by the concept of “tone policing”, particularly in the environmental movement, which has historically been white supremacist. A colleague of mine in Oakland once told another colleague that she might be more successful if she changed her tone. I was struck when she told him not to “tone police” her, and in the context of intentional work we were doing on racial justice, I saw the opportunities for positive change, even if the interaction were characterized by what Emily Post would describe as “bad manners” on both sides.

Let’s say yes to bad manners more often in the cause of intersectional justice, particularly when they’re used strategically. I’ve been guilty of tone policing on campaigns work in the past, myself, but I’ve committed to getting better and it’s important stuff to think about.

*Like many indigenous cultural creations, the cartoon’s original version appears to have vanished from the Internet, but I’m grateful to its creator(s) and would love to give them credit if you can help me track them down via Pinterest. I reached a dead-end after 20 minutes 🙁