I’ve been watching a couple of television shows by a writer called David Milch since my friend Lee lent me his book. Mr. Milch wrote his memoir, Life’s Work, after his Alzheimer’s diagnosis. As far as I can gather he wrote some of it in a care home during Covid. On that basis alone it’s an incredible achievement but it also says a lot about writing: It’s a reach. When I’m at full stretch I’m often groping around in the dark like I’m trying to remember something. It doesn’t even have to be a thing that happened. I wish I was as good at other things as I am at this thing because then I could explain it in simpler terms. But again, that’s writing. You can’t replicate it in other ways. It only works in your exact words in the order you put them down.

When people hire writers they tend to assume we’re craftspeople and we are. But there’s more to it. When I meet a client who values good writing and the time and energy it takes to pull it off, I can do more than knock words out. I can expand your idea and vision of who you are and what your life and work means to you. It’s not a boast. It’s a delight to go through that process with a person. I enjoy it and my clients do too.

My mum has Alzheimer’s and like many children of such patients I’m scared I’ll get it in the end. It’s a particularly cruel disease for somebody whose life has revolved around words. Imagine waking up in the morning no longer able to recite your favorite poems.

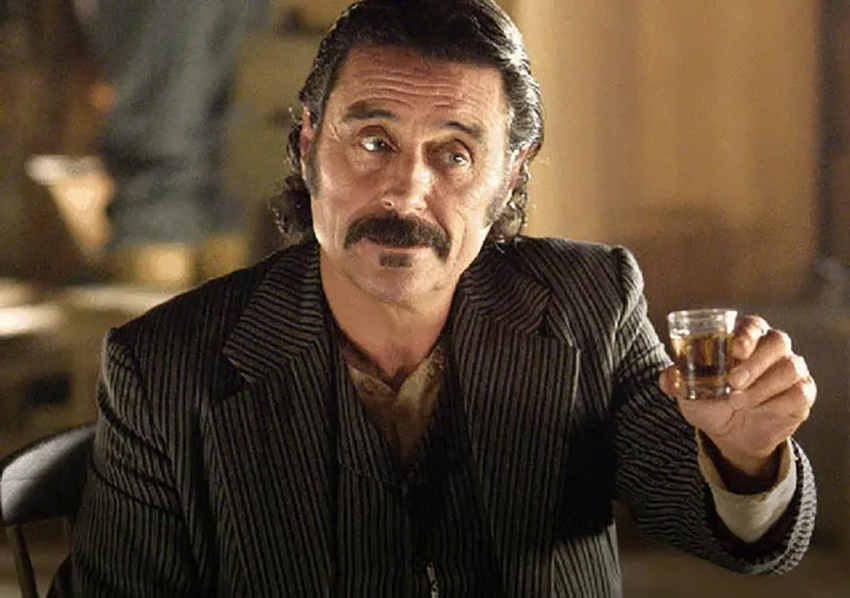

Mr. Milch wrote a show called Deadwood, set in the Old West. It stars the actor Ian McShane as a tavern owner. I hate Westerns but I do love Ian McShane. My mum does too. He starred in a 1990s BBC show about an antiques dealer called Lovejoy. We used to watch it every Sunday night and his charm and crookedness shaped my personality. In Deadwood, McShane plays darker but he’s still a charismatic and charming murderer. As my wife and I have watched the show over the last few days we keep commenting: there’s a lot of vagueness. Characters might hint at their intentions or talk to themselves. They might quote religious scripture and have a seizure. They might wear a longing expression or be in the grips of some past trauma as they’re processing the now. But the vagueness makes the writing and the show more intriguing, not less good. It’s studied vagueness. You need an incredible ear for realistic dialog to get to it or it would fall flat. Milch lived on the set of the show and would often rewrite a scene after seeing it performed, based on feel. He didn’t always know why he made a character say a given thing. It’s compelling to watch because of that confidence in the writing to try for subtlety.

A later show of Milch’s, Luck, stars Dustin Hoffman as a recently-paroled gangster. Like Milch himself, Hoffman’s character is a compulsive gambler. He is also starting to lose his memory and his confidence in himself and says so. At the end of every show, Hoffman’s character sits on a bed, drifting off to sleep while he talks with his number two. Their conversations feel more like a conversation between an old married couple. They miss words and sentences but there’s a feeling of intimacy and reflection to them. The scenes always conclude each show and make for theatrical watching. I always looked forward to them. The show wasn’t renewed for a second season, which is a shame. Horses died on set.

An earlier show was NYPD Blue which I’m still yet to watch. But knowing that it’s what Milch became best-known for, I’m excited to try it after Deadwood. Good writing makes good writing happen and so I try to read and watch as much of it as I can to keep my mind reaching in that way. None of us knows what the future holds but I’m less scared of Alzheimer’s as a result of reading this man’s book and watching his work. Some of the best words happen in the grey area between making sense and the other thing. That’s something to aspire to in one’s writing and as one tries to express oneself in the world.

Matt Davis is a strategic communications consultant in Manhattan.